|

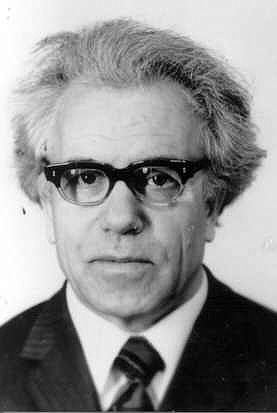

Vasily Brodov

- Russian Philosopher and Yoga Practitioner

Who

are yogis? Twenty years ago the answer to this quesion sounded

something like this: "Indian herments and fringe elements

who can sleep on beds of nails, tie themselves into knots

and stand on their heads". But today yoga is popular

among trendy Russian youth. No fashionable fitness club in

Moscow or other major cities can do without a yoga instructor,

and one may even find queues for yoga mats at sport shops. Who

are yogis? Twenty years ago the answer to this quesion sounded

something like this: "Indian herments and fringe elements

who can sleep on beds of nails, tie themselves into knots

and stand on their heads". But today yoga is popular

among trendy Russian youth. No fashionable fitness club in

Moscow or other major cities can do without a yoga instructor,

and one may even find queues for yoga mats at sport shops.

Prohibited

during the Soviet times, yoga is becoming very popular in

Russia. In Moscow and St. Petersburg alone, according to the

publisher of the Russian version of "Yoga Journal",

there are at least 100,000 people who practice yoga regularly.

Among them is even ex-President Dmitry Medvedev! Having told

Tainy Zvyozd (Secrets of the Stars) magazine that he

can even do a headstand (shirshasana),

Mr Medvedev stirred up a surge of enthusiasm both among long-time

yoga fans and neophytes who decided to commit to this physical

and spiritual discipline that is not a traditional part of

Russian culture.

Nowdays

there are no restrictions and obstacles for yoga practice.

Few people remember the Russian trailblazers who mastered

yoga on their own from translated books ("zamizdat")

and tried to share their knowledge and skills with other people.

During the Soviet regime the price of this could be losing

a good job, material well-being or even one's freedom. Professor

Vasily Brodov, the Chairman of the Yoga Association of

the USSR, had first-hand experience with all of this.

However,

his path towards Indian philosophy and yoga was not an easy

one. A native of Moscow, Vasily Brodov was born of 1912 in

Tzarist Russia. After peaceful February 1917 revolution followed

by October overthough Brodov's family survived dificult post-revolutionary

times followed by famine and civil war. At first young Vasily

studied in technical colledge, but then he realized his creative

nature and entered newly formed famous Moscow Institute

of Philosophy, Literature and History which he successfully

graduated in 1933 alongside with such famous poets, writers,

scientists and philosophers like Alexander

Tvardovsky, Alexander

Zinoviev, Arseny Gulyga and many others. Although he never

even dreamed in those times that Indian philosphy, culture

and yoga would become the mainstream of his life. In 1937

gravitation towards free thinking and participation in intellectual

gatherings led Vasily Brodov, a young philosophy teacher at

the time, to the infamous GULAG prison camps. In 1939 as a

prisoner he participated in the Finnish war between U.S.S.R.

and Finland. Then after the outbreak of Nazi invasion of U.S.S.R.

in 1941 Brodov continuously again and again applied to be

sent to the frontlines. At first, the GULAG administration

replied with an unequivocal "no," but as the situation

at the front became more desperate, political prisoners were

allowed to join penal battalions fighting in the most difficult

areas of the front. After Vasily Brodov was wounded, shell-shocked

and miraculously survived, he was transferred to a regular

artillery unit and marched from Karelsky peninsular to Berlin.

GULAG prison and fierce battles behind him, Brodov's severe

wounds after all served as a lifetime reminder of his hard-knock

youth as he "paid his dues to the Motherland with his

blood".

Interesting

to note that even during the war on the frontlines Vasily

Brodov's creative nature can't stop to expressed itself. He

wrote several poems and articles in the war newspaper "Stalin's

Fighter" which circulated in the troops. He even

accomplished a rather rare and really amazing military feat

documented in the rewarding list: during enemy's diving

bombers attack "by accurate and uninterrupted operation

of PPSh-41

machine-gun" he gunned down a Nazi diving bomber

Junkers

Ju 87 Stuka. He was rewarded the medal "For

Braveness" for this feat which was equal to the Order.

Such cases were extremely rare because it was a simple machine-gun,

diving bomber was moving in high speed and was hit at the

bottom of the dive. "My grandfather told me that he took

one hundred meters ahead because he perfectly undertood it

was a high-speed flying target. This was the secret of his

success. He always tried to get ahead of events, to express

his originality and to be a true pioneer in all areas of life

be it Indian philosophy, yoga practice, literature, poetry

or shooting down a diving bomber. He was very creative, original

and versatile person", recalls his grandson.

Even

after the Second World war life of Valisy Brodov was not a

bed of roses. Having finished his post-graduate studies at

the Institute of Philosophy, USSR Academy of Sciences, he

defended his thesis on a subject that was in high demand by

the Communist regime (dissertation work "John Dewey's

instrumentalism in service of the American reaction").

However, in 1947 he was practically exiled from Moscow to

the city of Saransk and worked there till the death od Stalin

in 1953 as an assistant professor in the philosophy department

of Mordovian Pedagogical Institute (nowdays the Mordovian

State Unversity). Then he was transferred from one institution

of higher learning to another as deemed "unreliable"

as Soviet society was very suspicious to ex-GULAG prisoners.

After exile, the talented lecturer became a teacher of philosphy

at

Moscow Art Institute

named after Surikov (1953), then Second

Moscow State Pirogov Medical Institute (1956), and

then the department of dialectical and historical materialism

of the natural sciences division of Lomonosov

Moscow State University (1962 - 1966). Brodov's "philosophical

brothers-in-arms" recall these years as "the most

fruitful time of his academic and teaching career" (Professor

G.Platonov). Even

after the Second World war life of Valisy Brodov was not a

bed of roses. Having finished his post-graduate studies at

the Institute of Philosophy, USSR Academy of Sciences, he

defended his thesis on a subject that was in high demand by

the Communist regime (dissertation work "John Dewey's

instrumentalism in service of the American reaction").

However, in 1947 he was practically exiled from Moscow to

the city of Saransk and worked there till the death od Stalin

in 1953 as an assistant professor in the philosophy department

of Mordovian Pedagogical Institute (nowdays the Mordovian

State Unversity). Then he was transferred from one institution

of higher learning to another as deemed "unreliable"

as Soviet society was very suspicious to ex-GULAG prisoners.

After exile, the talented lecturer became a teacher of philosphy

at

Moscow Art Institute

named after Surikov (1953), then Second

Moscow State Pirogov Medical Institute (1956), and

then the department of dialectical and historical materialism

of the natural sciences division of Lomonosov

Moscow State University (1962 - 1966). Brodov's "philosophical

brothers-in-arms" recall these years as "the most

fruitful time of his academic and teaching career" (Professor

G.Platonov).

In

1966 Professor Brodov became the Head of the Department of

Philosophy in All-Union

Institute of Civil Engineering (nowdays Moscow State University

of Civil Engineering) and worked there for 30 years

almost till the end of his life. He tought different disciplines

of philosophy - methodology, history of philosophy, epistemology,

logic, ethics and estetics, etc. - to teachers and students

alike and was widely recognized as a known philosopher professor

and blilliant lecturer and speaker.

After

the independence of India from the British colonial rule and

emergence of a new state, the Republic of India in 1947, Vasily

Brodov came to know more about India and Indian philosophy.

The overall idea to undertake academical research of Indian

philosophy was suggested to him by eminent Soviet academician

and ideological functionary

Georgy Alexandrov, his alumni, director of the Institute

of Philosophy , USSR Academy of Sciences. Vasily Brodov was

fortunate enough to study together with him in the the famous

Moscow Institute of Philosophy,Literature and History.

The subject of his doctor's thesis was "Progressive

social and philosophical thought in India in Modern Times

(1850 - 1917)". He successfully defended it in 1964.

Brodov's dissertation was a tremendous breakthrough not only

in Soviet Indology, but it was also recognised by well-known

German Indologist Walther

Ruben as the first systematic research into the

history of Indian philosophy in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries. On the basis of his doctorate thesis he wrote a

book "Indian

Philosophy in Modern Times", it was translated

into English and distributed by Soviet "Progress Publishers"

in India and worldwide (with two editions) in 80-s. This

book became a real bestseller in the category of philosophical

research in the history of Indian philosophy and even nowdays

you can buy it on Amazon.com!

One

notable event in his life was a meeting with Indian President

Sarvepalli

Radhakrishnan in 1964 at Moscow State University.

Professor Brodov delivered a welcome speech for the President

of India and gave him a copy of the book he compiled and edited

himself "Ancient Indian Philosophy: The Early Period,"

the first in the series "Philosophical Heritage".

This book was a translation from Sanskrit of the famous Upanishads,

ancient Indian texts. A team of translators worked on the

book, and Professor Brodov, who also studied Sanskrit under

well-known linguist Professor V.A.Kochergina, author of famoust

Sanscrit-Russian dictionary, wrote the preface and scientific

commentary on the ancient Upanishads.

The

new subject matter steered the recently awarded doctor of

philosophical sciences on a right track. In 1966 he became

the Head of the philosophy department of the All-Union

Institute of Civil Engineering. Talanted researcher continued

his studies in Indian philosophy and as an academic secretary,

participated in preparing for publication of six volume work

"The History of Philosophy". Brodov penned individual

chapters and it was published in full in 1965.

In

the early 1960s, one special even happen in the life of Vasily

Brodov: he was fortunate to meet a renowned Indian guru

Dhirendra

Brahmachari, yoga teacher of Indian Prime Minister

India Gandhi, who visited Moscow. He was invited to visit

the USSR to research the possibility of applying Indian yoga

to train Soviet cosmonauts to extend the time spend on the

cosmic orbit. Yogic asanas and pranayamas might be helpful

in this extention. Dhirendra Brahmachari gave lectures and

delivered practical lessons in closed sessions to Soviet cosmonauts,

which Brodov was able to participate.

Interacting

with the famous guru, mastering asanas and pranayamas had

an almost immediate salutary affect on the former frontline

soldier's health. Professor Brodov called yoga the "fruit

of the creative genius of the Indian people". He dedicated

the rest of his life to promoting it in the U.S.S.R. and took

every opportunity to impart Soviet people with some knowledge

of this ancient self-healing art, despite official disapproval

from the authorities. From 1973 to 1989 yoga practice was

officially banned by Soviet regime for ideological reasons

as "Troyan horse of Indian idealism". And from time

to time, he was able to cut through the Iron Curtain!

"My

grandfather Vasily Brodov stood at the epicentre of the struggle

for official, albeit indirect opportunities to study and promote

yoga in the U.S.S.R.," said Aleksey Brodov, grandson

of Vasily Brodov, also a researcher and Indologist. "I

recall his constant efforts to help Soviet people to know

the basic principles of yoga, how to start yoga practice with

little information available during the ofiicial Soviet yoga

ban. He was a real Guru for Soviet people in this information

vacuum created by Soviet buerocrats and short-sighted ideological

bonzas who banned dessimination of genuine information about

long-standing positive effects of yoga practice on human health".

Intersting

to note the real history behind the article "The

Teachings of Indian Yogis and Human Health in Light of Modern

Science," which was published in the book "Philosophical

Issues in Medicine." (1962) and was co-authored by

Vasily Brodov. In fact, this book was the first official

publication on yoga after the Second World War in the U.S.S.R.

published with the approval of the Ideological Department

of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party. Soviet

buerocrats were concerned about going seepage of information

about yoga into the Soviet Union which was a consequence of

political friendship, cultural and economic cooperation with

new Republic of India.

Communist

ideologists tried to ban systems of personal human development

for Soviet citizens, from Indian yoga to Chinese wushu, because

they were in contradiction with different mental limitations

and ideological restrictions which were artificially imposed

and cumbered the intellectual and physical growth of Soviet

people.

"Through

the practice of yoga, my grandfather Professor Brodov by that

time had genuinely improved his health, which had deteriorated

in GULAG, in penal battalion, at the frontlines as well as

in his post-war exile," said Aleksey Brodov. "Being

the actual exponent of the state order, he nevertheless understood

that his task created real opportunity to provide at least

some information about Indian yogic tradition in this government

publication. As a result, this article became the first official

publication on yoga since the death of Stalin and under the

Soviet system in general, giving it a unique place in the

history of yoga in the Soviet Union."

This

opened the door to a long series of different articles by

Vasily Brodov on Indian yoga in various magazines and newspapers,

including the authoritative "Scientific and Atheistic

Dictionary," (Moscow, 1969) and the magazine "Science

and Religion" (1962, No. 4). Professor Brodov was

also the co-producer and chief consultant of the famous Soviet

documentary "Indian

Yogis. Who are they?" (1970) which created

a volvanic explosion of interest to yoga in the U.S.S.R. It

was screened in the Sovit Union, Bulgaria and India and included

information about asanas, pranayamas, suggestology and hypnosis

methods by Georgy Lozanov and even parapsychology and telekinesis

experiments carried with phenomenal Soviet woman Kulagina.

However, only short 50-minutes version was available for a

general Soviet public, censorship thoroughly edited the material

and excluded any mention of parapsychology and other mental

experiments carried out in secret Soviet laboratories.

After

yoga ban by Soviet authorities in 1973 this documentary was

shelved for many years. Later Vasily Brodov wrote on the making

of this documentary and subsequent reaction to it: "The

years of personality cult and stagnation in our country were

also a time of strong negative attitudes towards yoga practices.

The official line stated that yoga, from the point of view

of its philosophy, is pure idealism, religion, mysticism,

and in practice, it is quackery, hoodoo and acrobatics. We,

as the filmmakers, had the intention, at first, to introduce

to the Soviet people a unique phenomenon of ancient Indian

culture, and, at second, to prompt our scientists, especially

those from biological and medical sciences, to think about

the human potential." Thirdly, we wanted to motivate

the experts to extract the rational seed from yoga that could

serve as an additional source of health. Unfortunately, for

ideological reasons during the period of stagnation, the intention

did not meet with our expectations. The more influential officials

at the Ministry of Health and the State Committee for Sport

had an unequivocal reaction to the documentary. They called

it the propaganda of idealism and religion. The result of

this criticism was evident: they crucified yoga as not our

Soviet ideology and it was banned for many years from the

public areas of life."

In

the early 1970s, a group of scientists and other public figures,

including Vasily Brodov, tried to influence Soviet System

wrote an open letter to General Secretary of the CPSU Central

Committee Leonid Brezhnev and Chairman of the Council of Ministers

of the USSR Aleksey Kosygin with a request to officially legalize

yoga and establish a yoga therapy scientific research institute.

Many well-known medical doctors, scientists, journalists and

cultural figures signed the document. However, the initiative

produced no visible results at the time. There was no even

a short reply from party bonzes.

"However,

not all Soviet people shared the opinion and motives that

led to the ban," recalled Vasily Brodov later, in his

tenure as president of Yoga Association of the U.S.S.R.,

which was created in 1989 in the wave of "Perestroyka"

and "Glasnost".

"Many people practiced hatha yoga on their own at home

and in private. Translations of foreign literature the so-called

samizdat (the secret publication and distribution

of government-banned literature - ed.) served as

instructional aids. Following the Perestroika years, "yoga

health groups" started popping up everywhere like mashrooms

after summer rain. Among the leaders of the groups, the more

enlightened and gifted ones became real yoga teachers and

self-proclaimed gurus."

It

is true that after the collapse of the Soviet System a new

openness brought a lot of rubbish to the surface. Among those

who called themselves "gurus" there were many "pseudo-gurus",

people who had no connection with real yoga just looking to

make money. Professor Brodov did not want to be associated

with these people in any way. As a result he resigned from

his chairmanship and, after all, the Yoga Association finally

collapsed after the disintegration of the U.S.S.R. Despite

not holding an official position, Vasily Brodov remained a

recognised authority on yoga theory and practive among Russian

practitioners. Incidentally, in the 1990s, in the so-called

"era of hard times," in his twilight years, Brodov

said that the revival of Russia would only be possible on

a path of growing nationalist sentiment, as he drew clear

parallels from the Indian independence movement. He was sure

that modern Russia could succeed by replicating the Indian

experience of revival and the retention of its nationhood.

At

first glance, the most paradoxical aspect of Vasily Brodov's

biography is the fact that he never visited India in his life.

However, this is easily explained. One only need consider

the times in which he lived and created his works! His friends

and relatives recalled that in the 1970s, he was frequently

invited to philosophical conventions abroad, including those

in India, but for some reasons, perhaps, because of his time

in GULAG or because of the secret programme of yoga practice

for cosmonauts he was not allowed to leave the U.S.S.R. Brodov

received the last invitation to visit India in the early 1990s

from the Ramakrishna

Mission Institute of Culture. But his health no longer

allowed him long distant flights, and he never did see geographical

India with his own eyes. Nevertheless, his colleagues noted

that inspite of a hard life, Vasily Brodov always remained

good-natured and cheerful personality with a very subtle sense

of humour. He maintained his physical and mental health with

daily yoga exercises and overall physical activity.

Professor

Brodov wrote: "Yoga is a system of self-regulation and

self-improvement of human personality, and here I can refer

to my own experience. After WWII I returned wounded, shell-shocked

and ill from the front lines in 1945. The doctor who prescribed

my medicine reassured me, "You've got another 10 or 15

years to live..." Unfortunately, prescribed medicine

helped very little. Illnesses that became more acute, cardiac

insufficiency, radiculitis, salt deposits, kidney stones and

many others forced me to try hatha yoga. Studying primary

sources and consulting with Indian experts helped me master

the elements of this physical therapy. As a result, all of

the ailments that were troubling me disappeared. They disappeared

without the aid of doctors or medicine. Today, being 78 years

old, I give my heartfelt thanks and deepest respect to the

great people of India for giving yoga to humanity."

Today,

millions of proponents of yoga in Russia would concur. We

pay tribute to brave heroes of the past, true trailblazers

and pioneers what Vasily Brodov really was.

[

NT ]

Evgenia

Lents, New Delhi

Prabuddha

Bharata

Vedanta

Kesari

Vedanta

Mass Media

|