|

The

Language of Religion

Editorial

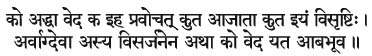

Swami

Satyaswarupananda

Who

really knows? Who in this world may speak of it? Whence this

creation, how was it engendered? The gods (were) subsequent

to the (world’s) creation; so who knows whence it arose’ (1)

The

Power of Language

The

search for a unified theory of physical forces has lead contemporary

physicists to explore high-energy states, for it has been

found that under extremely high energy conditions that are

presently obtainable only in specialized particle accelerators,

these forces tend to lose their distinctive identity. It is

therefore conceivable that under the extreme conditions that

prevailed when the universe came into existence (conditions

that one cannot, at present, even think of replicating experimentally),

the forces that we now talk of as distinct entities - gravitation,

electromagnetism, and the two nuclear forces - were all seething

indistinguishably in a ferment of intense energy. As the baby

universe expanded and cooled, these forces distilled out as

distinct entities as did the material particles associated

with them.

These

speculations about the early life of the universe, though

backed by empirical data, do raise some interesting philosophical

questions. What does this ‘distillation of forces’ mean? Can

we say that the law of gravity appeared at a point in time?

What ‘metalaw’ governs this process? Is it prior to time?

We

will not be exploring the answers to these questions here

but raise them only to highlight the process of conceptualization,

for though physics is associated with concrete objects in

the popular mind, theoretical physics is largely about concepts

(as is all the mathematics that underpins it), albeit concepts

that can be shown to work in the material world.

Now,

concepts are inextricably linked with language and it is in

and through language that the power of concepts is manifest.

What distinguishes the speculations of modern physicists from

those of their forefathers of ancient times is the former’s

ability to formulate their conceptions in precise mathematical

expressions - the language of theoretical physics - and then

generate specific and verifiable predictions from these formulations.

The power of mathematics, in turn, lies in the fact that it

works; even purely abstract mathematical concepts are found

to be effective in describing and predicting subtle and complex

physical phenomena.

But

why should mathematics be any more efficacious than ordinary

language (and thought) in apprehending the universe? If the

physical universe is somehow mathematically underpinned, there

is no reason why other forms of language should not prove

equally potent in sizing it up. Religious language, for one,

certainly lays claim to this potential.

Vak:

the Primordial Speech

The

Vedic rishis traced the source of language to Vak, the quintessential

speech. From the causal state devoid of all cognitions (apraketam

salilam) the primal volition manifested (kamastadagre

samavartata) as rita, the cosmic law, that gave rise to

Vak - ’Vagaksharam prathamaja ritasya vedanam mata amritasya

nabhih; Vak is imperishable, the first-born of rita, mother

of the Vedas, the source of immortality.’ (2) Vak is thus

identified with the manifest Brahman and mediates all knowledge

- 'Vachaiva samrad prajnayante, vag vai samrad paramam

brahma.’ (3)

Vak

is not to be equated with empirical speech or language (vaikhari

vak), for Vak is quadripartite: three of these parts lie

unmanifested within the depth of one’s being; it is only the

fourth that is spoken forth - ’Guha trini nihita nenggayanti

turiyam vaco manushya vadanti.’ (4) So the primal Vak

is also termed Para Vak or Shabda Brahman, at which state

of evolution the distinction between substantive material

objects (artha), their denominations (nama as word,

or shabda), and the mental concepts and cognitions relating

to these (pratyaya) are all indistinguishably intertwined

in the primordial soup, the apraketa salila. This Para

Vak evolves through the stages of pashyanti and madhyama

before manifesting as audible sound (dhvani) and the

phonemes (varnas) that go to build language. Pashyanti

is unformed (nirakara) language, where forms of objects

and the sequences of words have still not crystallized; yet

this is the very language and insight of the heart (dhi)

that the rishis visualize as mantras. Madhyama corresponds

to our mental language that is linked to our thoughts, of

which we become aware while ruminating in quiet and which

is resorted to actively during mental japa of one’s mantra.

(5)

In

this cosmocentric view of language and its referents, shabda,

artha and pratyaya are all derived from one

common source that is linguistically designated Para Vak.

It is this link that accounts for the veridical efficacy of

our thoughts and language. The Vaiyakaranas (Indian grammarians),

Mimamsakas, and Vedantins take this link to suggest that the

relation between shabda and its meaning (artha)

is eternal, underived, and impersonal. They argue that this

relation cannot be based on convention (as is asserted by

the Buddhist, Jaina and Charvaka thinkers, and also by modern

linguists) for the notion of ‘convention’ presupposes language

- the very thing claimed to be derived from convention. Language

is therefore taken to be beginningless and ever-existent (nitya).

(6)

Meaning

and Function of Religious Language

If

words are ontologically linked to their referents, are all

forms of vocalization meaningful? The pragmatic answer, on

which all Indian philosophical schools agree, is no, not at

the vyavaharika level of conventional usage. The practical

test of meaning is the ability of language to produce valid

knowledge (prama). The smallest unit of language conveying

unitary meaning (ekartha) is a sentence (vakya).

The words comprising a sentence must have logical interdependence

(akangksha), contiguity (asatti), and consistency

of meaning (yogyata). These, along with the capacity

of the sentence as a whole to give rise to a cognition in

the listener (tatparya), are the determining factors

of semantic validity. If any of these is missing, then the

sentence is unlikely to be comprehensible. Moreover, for a

verbal testimony to be valid, it must not be contradicted

by other means of knowledge like perception and inference.

(7)

Religious

language, however, differs from the language of ordinary use

in dealing with transcendental subjects and issues of ultimate

concern (the paramarthika level). Even when put to

pragmatic use, as for instance in the mantras one utters during

puja offerings, the meanings and connotations derived by the

user may be very different from what is revealed by the syntax

or what is obtained by ordinary grammatical analysis. Most

mantras are, in fact, meaningful only to the initiate. This

problem of meaning and function of religious language, especially

in the context of Vedic mantras, has been discussed by Yaskacharya

in his Nirukta, an etymological commentary on the Vedic

lexicon, Nighantu. (8)

The

issue is argued persuasively by Kautsa, who puts forward the

prima facie view that Vedic mantras are meaningless for the

following reasons: 1) Vedic texts are considered syntactically

fixed and unalterable, but in ordinary language a single idea

may be expressed in a variety of ways. 2) The use of Vedic

mantras in yajnas is directed by the Brahmana texts. If the

mantras were intrinsically meaningful, they would not be dependent

on other texts. 3) The Brahmanas contain passages like ‘Agnaye

samidhyamanaya hotaranubruhiti; To the agni that has been

lighted should the hota (sacrificial priest) address

thus.’ The use of such mantras by the adhvaryu (the officiating

priest) is meaningless, for the hota himself, being versed

in the Vedas, knows what needs to be done. 4) Then there are

mantras that contradict each other. For instance, one mantra

says: ‘Eka eva rudro avatasthe na dvitiyah; Rudra is

one alone, there being no other’, plainly in contradiction

to another: ‘Asangkhyata sahasrani ye rudra adhibhumyam;

Innumerable thousands are the Rudras that are over the earth.’

Or again, in one mantra Indra is described as ‘ashatruh, without

enemies’, while another says: ‘Shatam sena ajayatsakamindrah;

Indra defeated a hundred standing armies.’ Such speech is

not unlike that of the mad. 5) Some mantras are self-contradictory:

‘Aditirdyaur aditirantariksham aditirmata sa pita sa putrah;

Aditi is heaven, Aditi is the firmament, Aditi is the mother,

the father, the son.’ One individual cannot possibly be all

these simultaneously. 6) The meaning of many mantras is patently

inconsistent with facts. For instance, in the pashu-yaga

(Vedic animal sacrifice) a mantra is addressed to the sacrificial

sword: ‘Svadhite mainam himsih; O Sword, do not hurt

this (sacrificial animal).’ The animal is then sacrificed

using the same sword! 7) Finally, there are Vedic words like

amyag, yadrishmin, jarayayi, and kanuka that

make no etymological sense.

Yaskacharya

opens his refutation of these charges with the assertion that

Vedic words are no different from those used for secular purposes.

Hence, if the latter are meaningful, so are the former. If

there are rules for preservation of the integrity of Vedic

texts (the prohibition against syntactical alteration being

one such rule), secular language too is framed within a set

of grammatical rules for it to be comprehensible. The very

fact that the Brahmana texts endorse the use of these mantras

during rituals, argues Yaskacharya, is evidence of their validity.

The ritual function of the mantras must needs be evident for

them to be so prescribed. In fact the Brahmana texts only

help in choosing from a whole range of mantras the ones they

recommend for a particular ritual.

As

an example of the intrinsic meaningfulness of mantras, the

Nirukta cites a marriage mantra: ‘Ihaiva stam ma viyaushtam

vishvamayurvyashnutam, krioantau putrair naptribhir modamanau

sve grihe; May both of you, remaining unseparated in your

own house, attain fullness of age, rejoicing with children

and grandchildren.’

The

benedictive function that this mantra subserves is one of

the commonest uses that religious language is ordinarily put

to. Benediction is, of course, an indispensable component

of most religious ceremonies and sacraments. Another related

function of religious language is evocation. The Vedic hymns

comprising shastra and stoma, stuti and

stotra and the category of Vedic texts termed arthavada

(eulogy) - all serve to invoke and praise the Divine and to

evoke feelings of the sacred.

The

directions of the adhvaryu to the hota are an

example of the normative use of religious language. Yaskacharya

draws a parallel to the common norm of greeting one’s elders

by announcing one’s name and gotra (lineage or surname)

even when these are known to the former. Such injunctions

form the basis of personal and social discipline although

they may at times be misused as tools for extracting privilege

and exercising control.

The

mantra pertaining to Aditi is an example of the multiple levels

of meaning inherent in language use. When the constitutive

clauses are so plainly contradictory that a denotative meaning

(shakyartha) is impossible, secondary meanings have

to be derived by implication (lakshana). Metaphorical

language (upacara) is, in fact, a very potent tool

for religious expression since the transcendental elements

of religion are beyond our ordinary cognitive experiences,

and hence not very amenable to direct denotation. The metaphor

subsumes both symbolic expression and analogy. The injunctions

for upasana and worship are, of necessity, framed in symbolic

language like ‘adityo brahma ityadeshah; the sun is

Brahman - this is the instruction’, or ‘shalagrama girir

vishnu; the shalagrama stone is Vishnu.’ The stories

of Sri Ramakrishna and biblical parables have a powerful effect

on the mind because of their illuminative analogies. Sri Ramakrishna’s

analogy of water and ice, for instance, was enough to silence

the then hot debate about whether or not God had form.

The

paradox is a singularly powerful metaphor for expressing the

inexpressible. Brahman is beyond all conceptual and verbal

categories. Expressions like ‘Asino duram vrajati shayano

yati sarvatah; Though sitting still, It travels far; though

lying down, It goes everywhere’ are meditative tools for breaking

our conceptual barriers and directly apprehending the ineffable

Reality that is our own Being. The koans used by Zen masters

also fall in this category and serve a similar purpose. Hakuin’s

‘Let me hear the sound of one hand clapping’ or Yeno’s ‘Show

me your original face before you were born’ are instances

of such impossible commands whose resolution can occur in

enlightenment alone. A series of negations is another comparable

contrivance. The Mandukya Upanishad’s description of

the fourth state of consciousness (turiya) is an apposite

example: ‘Nantah prajnam na bahishprajnam nobhayatah prajnam

na prajnanaghanam na prajnam naprajnam; (Turiya

is) not that which is conscious of the inner world, nor that

which is conscious of the external world, nor that which is

conscious of both, nor that which is a mass of consciousness.

It is not simple consciousness, nor is It unconsciousness.’

Then

there is the category of technical terms that calls for specialized

knowledge. The meaning of terms like amyag that Kautsa cites

as obscure can be obtained only from specialized texts like

the Nirukta. The apparent ambiguity about the number

of Rudras can be resolved, says Yaskacharya, if we know about

the special capacity of the devas to transform themselves

into multiple forms. The allusions to Indra waging wars also

cannot be taken literally if we know that, having identified

themselves with the source of all power, the devas can have

no enemies. The allegory of the conflict, then, is a simile

for the interaction between water and sunlight that results

in rain.

Finally,

the mantra for the sacrificial sword has a sacramental role.

Ahimsa, or non-injury, is an unequivocally spiritual imperative.

Thus yajnas like the pashu-yaga that call for animal

sacrifice in order to obtain some ‘less than ultimate’ gains

need to be appropriately sacralized if the sacrificer is not

to suffer from guilt. It is for this reason that Hindu scriptures

allow the killing of animals only for religious purposes.

(9) That the process of sacralization acts as a strong deterrent

to morally questionable behaviour is well highlighted by Sri

Ramakrishna’s advice to his disciple Surendranath Mitra to

offer to the Divine Mother the wine that he consumed regularly.

This simple act was enough to gradually lead Surendra to total

abstinence.

Religious

Language and Cognition

The

profound psychological effects of religious language are evidence

of its inherent power. The fact that it is often non-rational

does not detract from this inherent potency, for much of our

routine behaviour - determined by our instincts, emotions,

and intuitions - is non-rational. These aspects of our personality

cannot be reduced to discrete logical categories.

In

her article on the ‘Western Philosophical View of Religious

Language’ Dr Lekshmi Ramakrishnaiyer, following John Hick

and some other recent theorists, suggests that religious language

is non-cognitive; it serves to express emotions and feelings

or project ethical views and behavioural orientations, but

does not lead to any verifiable knowledge. The Vedantic theory

of knowledge controverts this view by accepting verbal testimony

as a valid means of knowledge. It agrees with Hick that for

cognition to be valid it must not be contradicted by any other

means of knowledge. It therefore makes bold to apply the same

criterion to religious language too. In fact, we are perpetually

testing, often unconsciously, all linguistic inputs that enter

our minds throughout the day against the testimony of our

senses and of our reason based on past experience. We suspend

judgement on the many things that we cannot immediately verify,

but we often need to act on uncertain factual claims, if only

to prove them false.

Our

emotions are not perceived as mental constructs (antahkarana

vrittis), but Vedanta reminds us that they still are

objects of immediate perception (sakshi pratyaksha).

If language did not possess the ability to evoke replicable

perceptions poetry, for one, would lose its universal appeal.

When Blake talks about ‘seeing the world in a grain of sand’

he is trying to convey what is, in essence, an ineffable perception.

Rabindranath Tagore writes:

I

remember, when I was a child, that a row of cocoanut trees

by our garden wall, with their branches beckoning the rising

sun on the horizon, gave me a companionship as living as

I was myself. I know it was my imagination which transmuted

the world around me into my own world - the imagination

which seeks unity, which deals with it. But we have to consider

that this companionship was true; that the universe in which

I was born had in it an element profoundly akin to my own

imaginative mind, one which wakens in all children’s natures

the Creator, whose pleasure is in interweaving the web of

creation with His own pattern of manycoloured strands.

(10)

Spiritual

language explores territories deeper than that of poetic emotions.

It deals with insight (and this includes the insight of the

poets) and intuition - levels that correspond to pashyanti

Vak - that are only poorly expressible through the medium

of verbal vaikhari, and which need to be explored in

the subjective depths of one’s being.

Granting

cognitive status to religious language must not, however,

be equated with validity. If religious language points to

supersensual verities, we need great mental discipline to

correctly apprehend this meaning. The subjective nature of

these meanings also calls for uncompromising intellectual

honesty if we are not to deceive ourselves into erroneous

interpretations. The lack of spiritual discipline and honest

intellectual rigour is a major cause of theological conflicts.

These are the major tools for revealing the import of the

language of religion just as mathematical rigour is indispensable

for theoretical physics to make valid predictions about physical

phenomena. Without them religion turns into meaningless dogma

that is then made ‘meaningful’ through inane conflict. Chiselled

with these, religious language opens up our insight into the

profound and uncluttered simplicity of our being, a simplicity

so eloquently expressed in Basho’s haiku:

When

I look carefully,

I

see the nazima blooming.

By

the hedge!

References

1.

’Nasadiya Sukta’, 6.

2.

Taittiriya Brahmana, 2.8.8.5.

3.

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 4.1.2.

4.

Rig Veda, 164.45.

5.

Vaikhari shaktinishpattir madhyama shrutigocara; Dyotitartha

tu pashyanti sukshma vaganapayini. - Mallinatha.

6.

‘Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies’, The Philosophy of

the Grammarians, ed. Harold G Coward and K Kunjunni Raja

(New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1990), 53.

7.

Dharmaraja Adhvarindra, Vedanta Paribhasha, Chapter

4.

8.

See Nirukta, 1.15-6.

9.

Ma himsyat sarva bhutani anyatra tirthebhyo.

10.

Rabindranath Tagore, Creative Unity (London: Macmillan,

1925), 8-9.

|