|

The

Concept of God in the Vedas

Swami

Tattwamayananda

(Continued

from the previous issue)

From

Many to One

At

the earlier stages of spiritual evolution and metaphysical

thought the Vedas mention the names of various gods and goddesses:

Mitra, the Sun; Varuna, the god of night and of the blue sky;

Dyu and Prithivi, the Sky and the Earth; Agni or fire god,

the friend of all; Savitri, the Refulgent; Indra, the master

of the universe; Vishnu (though not a major divinity in the

Rig Veda), the measurer of the three worlds; and Aditi, the

mother of all other gods (the Adityas).

Gradually,

however, we come across a tendency towards extolling a god

as the greatest, controlling all other divine entities. This

marks the progress of man’s concept of God or the ultimate

Reality from polytheism to monotheism, ultimately leading

to monism. That is why the Rig Vedic rishi asks: ‘Kasmai

devaya havisha vidhema? To what god shall we offer our

oblations?’ (1) And again, ‘Ko dadarsha prathamam jayamanam?

Who saw the first-born?’ (1.164.4)

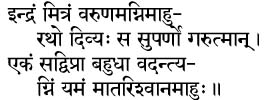

The

first mandala of the Rig Veda brings out this idea most beautifully:

‘They

(the men of wisdom) call him Indra, Mitra, Varuna, Agni, and

he is the heavenly, noble-winged Garutman. The Reality is

one, but sages call it by many names; they call it Agni, Yama,

Matarishvan (and so on).’ (1.164.46)

The

idea that names may be many and different but they all denote

the one God occurs in ‘Vishvakarma Sukta’ too. Therein it

is stated:

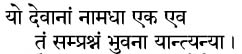

‘The

name-giver of the gods is one; other beings come to him to

inquire.’ (10.82.3)

Samprashnam

here refers to the two questions from the ‘Nasadiya Sukta’:

‘Kah veda? Who had known?’ and ‘Kah pravocad?

Who had announced?’ These questions, which are in fact an

enquiry into the one impersonal, attributeless, formless Principle

behind all concepts of God, occur in the ‘Hiranyagarbha Sukta’

(10.121, cited above), in the Shatapatha Brahmana (‘Ko

hi prajapatih? Who is Prajapati?’), and also in the Aitareya

Brahmana (‘Ko nama prajapatirabhvat? Who became

Prajapati?’)

One

of the grandest conceptions of God in the whole of Vedic literature

is found in the last chapter of the Shukla Yajur Veda Samhita,

which is known as the Ishavasya Upanishad. It is said

that whatever there is in this world is to be filled and covered

with isha or Ishvara (ishavasyamidam sarvam).

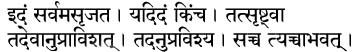

God creates this world, then enters into everything. The idea

is put forward even more forcefully in the Taittiriya Upanishad:

‘It

created all this that exists. Having created (that) It entered

therein. Having entered, It became the formed and the formless.’

(2)

The

Upanishad says that ‘It’ contemplated and projected (created)

the universe, and then entered into the created objects and

became one with both the manifest, gross and concrete creation

as well as the unmanifest, subtle and abstract.

The

universe is the abode of God. The Lord is the ruler of the

universe as well as its indweller. The various aspects of

gods and goddesses exist within the body of this Lord in their

subtle and causal forms. At this stage He is called Prajapati

or Hiranyagarbha. The concepts of Prajapati (the supreme Lord

of all beings) and Vishvakarma (the Creator in instrumental

mode) constitute an important stage in the conception of God

in the Rig Veda. The idea of a great deity who is the repository

of all power and virtue was a gradual and natural process

of growth.

Prithvi

is the feet of this Lord; antariksha is his belly;

dyu his head; the Sun and the Moon are his eyes; different

corners of the universe are his ears. The microcosm and the

macrocosm are the two dimensions of the same Ishvara. The

concept of Prajapati or Hiranyagarbha marks an advanced state

of monotheistic evolution of Vedic philosophy. The question

repeatedly raised in the famous ‘Hiranyagarbha Sukta’, ‘Kasmai

devaya havisha vidhema?’ shows that polytheistic conceptions

of the Godhead had been left behind by then.

Anthropomorphism

at an advanced monotheistic level is revealed in the ‘Purusha

Sukta’, which is widely used in a number of rituals. The sukta

says: ‘Purusha evedam sarvam, yadbhutam yacca bhavyam;

Purusha is all this world of movable and immovable objects.

He constitutes the past, the present and also the future.’

The

Purusha of the ‘Purusha Sukta’ is the manifested state of

unmanifested karana brahman. Possessed of an infinite

number of heads, eyes and feet, he has enveloped the whole

of his creation. He manifests as virat, the sum total

of all existence. Depicting the macrocosmic dimension of creation,

he reminds us of the essential unity and oneness of existence,

the unity of God and His creation. The ‘Hiranyagarbha Sukta’

announces: ‘Hiranyagarbhah samavartatagre bhutasya jatah

patireka asit; Hiranyagarbha was present at the beginning;

when born, he was the sole lord of created beings.’ (10.121)

From this stage it is only a small step to the Advaitic concept

of an ultimate Reality without name, form or attributes.

The

Concept of God and Rita

Rita

is the cosmic order that guides not only the individual life

of man, but also the totality of universal life. So, a god

is sometimes called ritavan and a goddess ritavati.

The god Varuna is supposed to be the custodian of rita,

which, according to Vedic seers, is praised and glorified

even by the devas. The Rig Veda calls Vishnu ritasya

garbha, the embryo of rita. The dawn, the sun,

the moon, in fact the entire universe, is based on rita.

The twenty-third sukta of the fourth Rig Vedic mandala, addressed

to the god Indra, ends with the glorification of rita.

As a moral principle it encompasses the psychological life

of individuals. As the cosmic Order or eternal Law it is responsible

for the triumph of good over evil and light over darkness.

Rita integrates chaos into cosmos, gives order to the

universe and shows the righteous path for the mind to follow.

It is the psychological principle teaching man how to lead

a moral life. Thus we can see that according to the Vedic

seers, the same ideal functions as the guiding principle for

individual as well as universal life. That is why in the first

sukta of the Rig Veda itself, addressed to Agni, the sages

call their deity ritasya didivim, the illuminator

of truth.

The

Concept of Self-surrender in Vedic Literature

It

may be interesting to note here that even the concept of prapatti

or sharanagati (the path of self-surrender through

total subservience to God), usually associated with the bhakti

tradition, has its origin in the Vedas. This supreme ideal

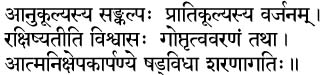

of devotion consists of six factors:

‘A

sattvic motive, abstinence from all kinds of disservice to

God, conviction and unflinching faith in the saving grace

of the Lord, seeking His grace, complete self-offering, and

longing for the earliest extinction of this worldly existence

constitute the six forms of self-surrender.’ (3)

The

‘Varuna Sukta’ found in the seventh mandala of the Rig Veda

is, perhaps, the origin of the ideal of self-surrender which

later became an essential element of Vaishnavism. In the first

four mantras the rishi is repeatedly asking Varuna to have

mercy on him, to bestow joy and happiness on him. He is craving

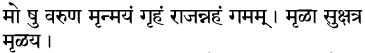

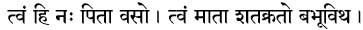

for mercy and favour:

‘May

I never go, royal Varuna, to a house made of clay; have mercy,

Almighty, have mercy.’ (Rig Veda 7.89.1)

The

word nyasa is often used to mean the sharanagati

ideal that is normally denoted by prapatti in Vaishnava

devotional scriptures. For example, it is said in the Taittiriya

Aranyaka that self-surrender is the highest form of

austerity: ‘Etanyavarani tapamsi nyasa evatyarecayat.’

(4) It is also stated that, ‘nyasa iti brahma, brahma hi

parah; renunciation is Brahma, and Brahma is the Supreme.’

(5)

Some

of the Vedic statements, which form the origin of the six

elements of the sharanagati ideal, may be identified

as follows:

‘He

is the sun dwelling in the heavens, the air dwelling in the

sky, Vasu (the appointer of the stations of all creatures)

in the mid region, the fire existing in the altar (the agni

on earth), the guest in the house; He dwells among men, among

the gods, in Truth and in space. He is born in water, born

on earth, born in the sacrifice, and born in the mountains.

He is the Truth. (He is the Great One.)’ (6)

The

idea of sattvic motives, anukulyasya sangkalpa, that

is reflected in the pervasive vision of the Supreme in the

above mantra, has been expressed even more forcefully in the

Rig Vedic shanti mantra beginning ‘Vangme manasi pratishthita

mano me vaci pratishthitam; May my speech be based on

(be in accord with) my mind; may my mind be based on my speech.’

The

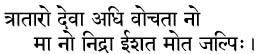

ideal of complete abstinence from all types of negative action

or disservice (pratikulyasya varjanam) is indicated

in the Rig Vedic mantra:

Saviour

gods, speak favourably to us; let not sleep, nor the censurer

overpower us.’ (8.48.14)

Similarly,

different aspects of the ideal of sharanagati are found

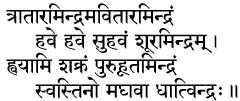

in the following Vedic mantras:

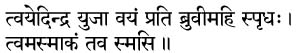

‘I

invoke, at repeated sacrifices, Indra, the preserver, the

protector, the hero, who is easily propitiated - Indra, the

powerful, invoked by many. May Indra, the lord of affluence,

bestow prosperity upon us.’ (7) (Faith in the saving grace

of God.)

‘O

Bounteous One! You are our father and mother.’ (8)

O

Indra, with you as our helper, let us answer our enemies.

You are ours and we yours.’ (9)

The

well-known shanti mantra of the Krishna Yajur Veda

beginning with ‘Saha navavatu; May He protect us’,

reflects the soul’s yearning to take refuge in God, goptritva-varanam.

Offering

prayers, performing Vedic rituals to various gods and goddesses

and leading an integrated life of pursuit of the path of artha

and kama without deviating from the path of dharma, in complete

harmony with nature and the rest of creation - this was the

guiding ethical principle of Vedic society. To understand

the idea of God conceived at the early stages of Vedic thought,

it is essential to take note of certain fundamental features

of the Vedic scheme of life. The social life portrayed in

Rig Veda reveals certain interesting features. Monogamy, sanctity

of the institution of marriage, domestic purity, a patriarchal

system, a just and equitable law of sacrifice, and high honour

for women were some of the noteworthy features of the social

life during the Vedic period. We find the Vedic seers praying

for fullness of life:

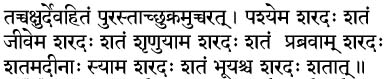

‘May

we see the sun rise a hundred autumns. May we live a hundred

autumns, hear (through) a hundred autumns, speak (through)

a hundred autumns, and be happy and contented a hundred autumns,

nay, even beyond these years.’ (10)

The

Origin of Advaita

In

the Bhagavadgita, Sri Krishna himself says that those who

are devoid of proper knowledge of the real purport of the

Vedas and the proper method of propitiating the Almighty,

are deluded by ignorance. They think that they themselves

are capable of performing Vedic sacrifices, even without the

help or grace of God. (11)

One

of the most striking depictions of the relation between the

macrocosm and the microcosm, the absolute and the relative,

the ultimate cause and its effect (karana brahma and

karya brahma) and the assertion that both are, in reality,

infinite, full and perfect, occurs towards the end of the

Shukla Yajur Veda Samhita in the shanti mantra for

the Ishavasya Upanishad beginning with ‘Purnamadah

purnamidam; That (supreme Brahman) is infinite, and this

(conditioned Brahman) is infinite.’

Several

portions of the Shukla Yajur Veda Samhita (for instance,

the ‘Rudradhyaya’) contain ideas that are strikingly Advaitic

in content and form. Some mantras of the ‘Purusha Sukta’ (which

occurs in the Shukla Yajur Veda as well) are interpreted

even by Sayanacharya in Advaitic terms. Commenting on the

mantra beginning with ‘Paridyava prithivi sadya itva parilokan

paridishah parisvah; Having gone swiftly round the earth

and heaven, around the worlds, around the sky, around the

quarters’, Sayana states: ‘Here the nature of jiva is Brahman.’

(12)

Similarly,

the Krishna Yajur Veda Samhita too is full of mantras

which have an Advaitic content. The Tandya Brahmana

and the Samavidhana of the Sama Veda are equally rich

in Advaitic ideas. So also the Atharva Veda.

The

literal meaning of Advaita has been explained by Madhusudana

Saraswati as ‘that in which there is no twofoldness’. Shankara’s

Advaita siddhanta is not only the climax of philosophical

speculation and the highest philosophy of ethics, but also

a way of life. As the culmination of man’s metaphysical contemplation

and spiritual evolution it is the natural final goal of our

spiritual sadhanas. In fact, some of the most beautiful Upanishadic

verses which Shankara has interpreted in the light of Advaita

occur in the Samhita portion of the Rig Veda. For example,

the following mantra traditionally associated with the Mundaka

Upanishad (3.1.1) is found in the Rig Veda as well:

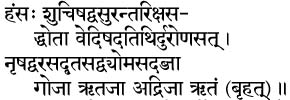

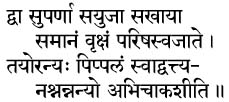

‘Two

birds that are ever associated and have similar names, cling

to the same tree. Of these, one eats the fruits of divergent

tastes, and the other looks on without eating.’ (13)

The

mantra brings out the essence of Advaita philosophy and the

identity of jiva and Brahman. The bird on the lower branch

is the jiva and the one sitting on the upper branch of the

tree as witness, without eating fruits, is God Himself. This

mantra shows that though its philosophical and logical perfection

is reached in Upanishadic literature, the origin of Advaita

philosophy is, in fact, to be found in the Rig Veda Samhita

itself.

The

well-known ‘Devi Sukta’ (10.125) is another striking example

of a Samhita mantra depicting Advaitic experience. The word

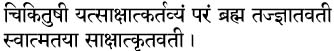

cikitushi in the third mantra of this sukta is explained

by Sayana as:

’She

(the rishi) had known or realized as her own Self the supreme

Brahman, that which must be realized.’

Innumerable

mantras of the Rig Veda Samhita have been explained

by Sayana in an exclusively Advaitic sense.

The

Rig Veda gives a great message in the first mantra of the

thirteenth sukta of the tenth mandala. This is perhaps the

most forceful expression of man’s divinity and immortality

found in the whole of Vedic literature. It runs as follows:

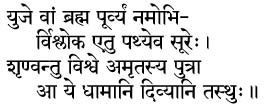

‘O

my sense organs and their presiding deities, I salute you

(that is, I merge you all with the eternal Brahman through

meditation). May this hymn of praise spread everywhere through

the medium of the wise. May you all, children of immortal

Bliss, and all those living in the bright (divine) worlds,

listen to me!’

The

famous ‘Nasadiya Sukta’ (Rig Veda 10.129) contains the most

sublime depiction of Advaitic monism that was later elaborated

upon in the Upanishads and expounded by the great Shankaracharya.

In this hymn all phenomena are traced to the one Principle

which is beyond opposites like life and death, existence and

non-existence, being and nonbeing, day and night, and so

on. The one Reality is neither existence nor non-existence;

it is beyond name and definition. The concept of maya, which

explains why the perfect Reality appears as this imperfect

world, has its roots in the ‘Nasadiya Sukta’. Here we may

very well remember that Advaita is, after all, a matter of

inner experience (‘anubhavaikavedyam; known through

experience alone’, in the language of Shankaracharya) and

not a subject for philosophical speculation.

The

‘Nasadiya Sukta’ is perhaps the most scientific description

of the ultimate Reality as well as of the projection of the

phenomenal world. It makes the relative and the Absolute,

nature and Spirit, the twin aspects of that one Reality and

shows that men of wisdom (kavayah), who had controlled

their senses, found out the ultimate cause of this world (which

appears to be real) in their own hearts (hridi) through

concentrated intellects (manisha).

References

1.

Rig Veda, 10.121.

2.

Taittiriya Upanishad, 2.6.1.

3.

Ahirbudhnya Samhita, 37.28.

4.

Taittiriya Aranyaka, 10.62.

5.

Ibid.

6.

Rig Veda, 4.40.5.

7.

Rig Veda, 6.47.11; Atharva Veda, 7.86.1.

8.

Rig Veda, 7.98.11; Atharva Veda, 20.108.2.

9.

Rig Veda, 8.92.32.

10.

Shukla Yajur Veda, 36.24.

11.

See Ramanuja’s commentary on Bhagavadgita, 15.15.

12.

Sayanacharya’s commentary on Shukla Yajur Veda, 32.12.

13.

Rig Veda, 1.164.20.

|